For a New Yorker, to tell a 9/11 story is to tell a personal one.

I was born here.

I live here.

I was at work here on that beautiful Tuesday morning 10 years ago. I was in the middle of engineering Doug Limerick’s 9 a.m. ABC NEWS network radio newscast when the second plane roared into the World Trade Center, forever changing our lives.

During these ensuing years, the nation has paused in solidarity with us here in New York, at the Pentagon and in rural Pennsylvania.

With hearts and hands joined, we have honored the nearly 3,000 people who showed up for a normal day’s work only to perish in the collapsing towers of the World Trade Center or the fireball at the Pentagon.

We salute the passengers of United Flight 93, whose selfless act of courage ― tail-spinning their hijacked airplane into a farmer’s field ― introduced the world to Shanksville, Penn., and heroically averted a tragedy at the White House.

Our 9/11 remembrances include those first-responders who ran into the chaos at Ground Zero, losing their own lives while answering the call for help.

We also honor those first responders who survived their grim tasks to be rewarded with health issues.

As the 10th anniversary approaches, the Presbyterian News Service takes a closer look at several personal 9/11 stories. They are drawn from suburban villages like Katonah, N.Y. They come from West-Park Presbyterian Church, my congregation, in the Presbytery of New York City.

Perhaps most importantly, 9/11 stories come from the surviving family members, such as my friend, Monica Iken Murphy, the courageous widow whose inner strength and hard-fought efforts helped make the 9/11 Memorial a reality.

The widow’s might

Monica Iken —Photo by Jim Nedelka

Ten years ago, she was just Monica Iken, newlywed.

On Sept. 11, 2001, she and Michael Patrick Iken had been married less than 11 months. That particular Tuesday morning began as had dozens of others: a good morning kiss for Michael in that half-awake state in which many a spouse sends off their other half to work.

“You said, ‘I love you, have a good day.’”

The words are from Monica’s eulogy for Michael, his memorial service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, his mourners still numb from the events of the previous week.

“…those words soothed me back to sleep.”

The couple had met by sheer accident (or was it divine intervention?) during Labor Day weekend, 1999, at a neighborhood restaurant called Park Place. He was celebrating his upcoming Sept. 8 birthday with his best friend. She and her best friend were out for a Saturday night on the town. He invited the ladies to join them for a drink, but they had other plans and declined.

Later, Monica would learn that after they left, Michael turned to one of his friends and said, “That’s the girl I’m going to marry.”

The following Saturday ― Sept. 11, 1999 ― Monica and Jen were again headed out. Already behind schedule, it was around 11 p.m. when they had to turn back: Monica had forgotten her ID.

This delay put a kink in their dinner plans, so the pair stopped in at Park Place. Monica noticed a lone man at the bar and sat down near him. While her friend ate, Monica struck up a conversation. The gentleman turned out to be the same guy ― Michael Iken — whose offer of a birthday beverage had been politely declined by the ladies the previous weekend.

Iken had had a hunch Monica might stop in that evening; he had been sitting there since about 6 p.m., waiting.

“He began telling me his life story, and the next thing we knew it was 3 a.m.,” she recalls.

They exchanged phone numbers. Within three months, he proposed. They moved in together that February and married on Oct. 27, 2000, each for the second time.

A warm smile crosses her face. “Everybody thought we were crArizy.”

Today, even though she remarried ― happily, to “a great guy” with two lovely young daughters ― Monica is not shy about telling anyone and everyone that Michael, a trader at Euro Brokers, was/is her soul mate.

“Not long afterward,” her eulogy continues, “the phone rung and I was startled to hear your voice. You said you were all right, not to worry and turn on the news. I said ‘Okay’ and turned on the news, in horror. You called again to assure me that you were safe and to call the family. I wished I could have told you to run from the building. To get out. But I didn't, I couldn't believe what I was seeing. You told me you were safe and I wanted to believe you. I never dreamt those would be the last words I would hear from you.”

Within a few moments Michael, in his office on the 84th floor of the World Trade Center’s South Tower, would become a cherished memory. Days later, co-workers would tell her he probably could have escaped but that he had gone back to help a co-worker who, scared out of her wits, had taken refuge under a desk.

Along with a brother and a sister, Monica was raised in the Yorkville section of Manhattan’s Upper East Side by a single mother. Monica would grow up to become a New York City schoolteacher and marry her college sweetheart, but for whatever reasons two people can’t stay married, she was single again within five years.

But in 1983, Monica was a tall, skinny, energetic 13-year old go-getter.

My wife would often sit on our stoop holding our six-month-old son, taking in the afternoon sun while waiting for me to come home from work. And there would be Monica, stopping by with at least one friend in tow, “oohing” and “ahhing” at our son while getting in her pitch to babysit.

Eventually, but cautiously, Holly invited “Moni” to come on board, first as a “mother’s helper,” then graduating to babysitter, continuing when our daughter came along. As Monica grew older, Holly invited her to participate in childcare at Central Presbyterian Church. She ultimately stepped up to also teach Sunday School.

Through the years, the bond between Holly and Monica grew extremely strong. Both readily explain their relationship as mother/daughter close. Thus, it was no surprise that, on the morning after the attacks, when my wife answered the phone to the excited voice of a friend telling her that Monica was on TV outside a New York hospital holding a picture of her missing husband, Holly knew the only place to be that day was by her friend’s side.

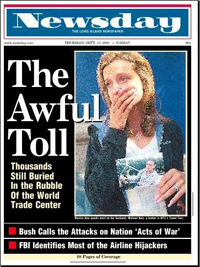

Monica’s heartbreak and anguish were captured in a photograph that became the Sept. 13, 2001, front page for Newsday, the Long Island newspaper.

: Front page of Newsday, September 13, 2001. —Photo courtesy: www.Newsday.com

She vowed that Michael ― and everyone else who perished that day ― would always be remembered, her gut instincts crying out to her that a memorial must be built on the 16-acre World Trade Center site.

“That site is very powerful. That’s where he was ― I’m drawn to it for that reason,” she says. “For the group of us who don’t have remains, not having a final resting place for our loved ones was so important in the beginning. My biggest thing was not being able to take Michael home, and I know that he would have wanted me to take him home.”

A memorial project on the footprints of the downed towers became her mission. She established September’s Mission, a not-for-profit organization that, according to its mission statement, works to “…support the development of a memorial park on the former World Trade Center site that ties into the overall redevelopment of Lower Manhattan” and is committed to “…working with the families, Manhattan residents, businesses and public officials to ensure that the future of the World Trade Center site not only honors the lives that were lost on September 11, but serves all New Yorkers for generations to come.”

The foundation’s efforts to bring about a bricks-and-mortar memorial began with a virtual one on its website, which allowed family and friends to post remembrances of their lost loved ones.

September’s Mission also hosted and supported events such as Christmas and Halloween parties where 9/11 families ― especially the children ― could strengthen personal connections within this unique community, creating a positive, nurturing forum for healing.

Appointed to a seat on the board of the World Trade Center Memorial Foundation with such luminaries as David Rockefeller, Robert De Niro and NY Jets owner Robert Wood “Woody” Johnson IV, Monica weathered the frequent storms and uphill battles of the early stages of this process.

With simple and clear reasoning ― “That site is powerful to me because that’s where he was. I want to be able to go there and honor him in that place where he was, not some foreign place” ― she was especially effective in turning around those who sought to redevelop the World Trade Center site while erecting a token memorial in another part of the city.

September’s Mission ultimately partnered with other 9/11 family groups, such as Voices of 9/11, but Monica Iken’s vision and voice remain clear and eloquent. Her efforts continue to be fueled by the same dedication, enthusiasm and old-fashioned New York City chutzpah that helped her land those early babysitting jobs.

While others may rush to claim ownership of the physical memorial, it is Monica’s mission and vision that gave the project a life and a soul.

“Michael is there. I have no remains,” she says. “If it had taken 20 years, I would have taken 20 years. It’s worth every minute, every second that I’ve spent on it. I wouldn’t change a thing. I would do it all over again the same way. The memorial and museum gives us a place to go to pay our respects and lets the world do that as well.

“There’s nothing more powerful than now being able to go there and actually see it to fruition … wow! The World Trade Center is hallowed ground,” she continues. “Souls are resting in a peaceful, reverent, reflective space now.

“I was blessed in my life with an angel, and God gave me the strength to do this thing and He told me, ‘You’re gonna do it’ and I said ‘OK, whatever You say I’m supposed to do, I’ll do,’ and I just did it, and He led the way.

“I’m so pleased that we accomplished it ― it’s a great feeling to know we did it … we did it for them.”

The Good Samaritans

Question: When you are a community of faith and a historic world tragedy happens in your backyard, what is your first response?

On Sept. 11, 2001, the congregants of West-Park Presbyterian Church found themselves searching to answer this exact question.

With Ground Zero’s billowing black smoke visible from the church’s front steps some five miles uptown, the Rev. Robert Brashear’s initial response was akin to that of other pastors in the city and around the world: open wide the sanctuary doors and be available to anyone wishing to talk. While a clutch of people with their private thoughts stopped by, Brashear gathered the session and began calling the membership.

“Happily, none of our members was killed or physically injured or lost a family member in the tragedy, but we all were impacted and all were of one mind: ‘What can we do to help?’” Brashear said.

Their answer began with peanut butter, jelly and 3,000 slices of bread.

The resultant 1,500 sandwiches led to the congregation’s invitation for a night of service at Ground Zero. A West-Park team spent 12 hours feeding relief workers at St. Paul’s, the 18th-century Episcopal chapel across the street from the World Trade Center damage.

Amazingly, beyond a smattering of broken window panes, the chapel where George Washington once prayed was spared from any significant physical damage.

West-Park’s post-9/11 “helping hand” efforts were not limited to that single evening of slicing onions and ladling jambalaya.

Like other churches within the city, West-Park’s balconies, gym and social hall soon became ad hoc dormitories for volunteer work teams.

“They came from everywhere,” remembers Brashear. “They didn’t know exactly what they were going to do, but they all knew they had to do something.”

Also arriving at West-Park Church, as well as at other churches throughout the five boroughs, was a flood of sympathy cards, teddy bears, hand-made banners, letters and drawings expressing their emotional support for New York’s healing. The ones from obviously young children were the most touching.

West-Park Church also provided a one-on-one avenue of caring for the Ground Zero volunteers.

The Rev. Reginaldo Braga, Jr., then the congregation’s associate for ecumenical ministry, was recruited as part of a team of chaplains coordinated by a disaster chaplaincy group. Working in affiliation with the Red Cross, the chaplains initially staffed a pair of “respites.”

St. Paul’s Chapel, immediately across the street from the World Trade Center, was staffed around the clock in the days following the attack, offering food, counseling and a place to rest and pray for emergency workers. —Photo courtesy: Leo Sorel, www.trinitywallstreet.org

Open around the clock, the respites offered rescue and recovery workers the opportunity “to come rest a bit, have refreshments and find mental health and spiritual care professionals available.” At shift’s end, each respite team ― which included a “mental help person” and a chaplain ― debriefed with the chiefs of mental and spiritual care.

In an e-mail, Braga vividly describes his experiences, especially after one respite “was deactivated, leaving only us and the morgue, by the river near the fallen buildings … right at (what the volunteers referred to as) the ‘pile.’”

Braga remembers the sometimes “very difficult task of orchestrating ‘togetherness among the various agencies.’ Inevitably, there was tension. The exceedingly high need to help exhibited by some volunteers was a concern of indication of mental and spiritual need of the volunteer him/herself and a potential source of tension in the highly stressed context.”

Braga recalls one instance where stress boiled over into a flare-up with a military chaplain “not part of our Red Cross team who was not only proselytizing, but voicing openly revengeful statements against Muslims.”

Yet, he adds, much of the time spent was simply about “passing the time.”

“I used to have conversations with fire-workers, police, and other rescuers about the most mundane things: how the baseball or basketball games had gone, what they meant for life and hope, etc. A lot of the work was to anchor a sense of ‘normality.’”

Through his listening to the volunteers, Braga was struck by the enormity of the gift being returned to the chaplains and mental health workers: the gift of hope, unearthing it, as he puts it, “from the deepest chambers of our hearts as they continued to serve hours and hours without stop at the ‘pile.’

“I remember one rescue worker showing me some pictures that he had with blurred lights, a sort of blurring of night photography that shakes which, for him, clearly showed angels all around the area. For him, they were surrounded by angels!”

Soon, there would be another band of Earth-bound angels stepping-up to lend a hand.

As part of the world’s response, funds came into the Presbytery of New York City with the aim of helping those “falling through the cracks” of the ongoing relief efforts. The intended recipients: those who did not have the high profile of the white collar workers in the World Trade Center.

Each “hub church” would be available to assist the bus boys, dishwashers, delivery crews and other workers ― or their families ― from the restaurants, coffee shops and other small businesses in and around the twin towers’ neighborhood.

The presbytery turned to West-Park Church to become a hub church.

“The funds came with specific requirements, such as the amount of office space required, a phone line and available staff to handle this task,” recalls Elder Angela Willey, the congregation’s coordinator of events and volunteers. “The congregation’s Ground Zero experience, Braga’s chaplaincy connection and West-Park’s legacy of social justice ministries all played into the decision making.”

The Rev. Bob Brashear and Elder Angela Willey of West-Park Presbyterian Church serve communion. —Photo by Jim Nedelka

The hub church process was relatively simple. When the presbytery received a 9/11 needs call ― usually clients seeking one-time assistance ― they referred the caller to West-Park. There, Willey or a volunteer would conduct an interview to determine what aid was necessary.

Looking back across nearly 10 years’ time, Willey remembers that most of those who came through were folks who had worked at the World Trade Center but, in the wake of the attacks, didn’t fit the criteria required of FEMA or other agencies. She is still a bit puzzled why West-Park only processed what seemed like a handful of “hub church” requests.

“Most of those who I remember were immigrants,” she recalls. “They had papers, but they may not have known the system as well.”

Willey applauds the hub church program’s noble “Good Samaritan” intent as a gut response to everyone’s need to help. “When stuff like that happens, yeah ― you respond!”

Yet, she is also a bit wistful about where the efforts could have gone. Because of the nature of the program, there was no way to follow up with those who were helped. She wonders if some of the needs remain.

“I don’t know if we made a difference ― I hope we made a difference,” she says adding that, under the circumstances, she isn’t sure any organization from any religious group could have done any better.

“It was such a crazy time. I wasn’t waiting for anyone to come back to say thank you.”

9/11 plus ten

What is ingrained in our humanity that moves us to honor what we call “round number” anniversaries? Why is a child’s eighth birthday seemingly a less significant event than their first? Why is a 15th wedding anniversary more cherished than a couple’s 12th?

What is ingrained in our humanity that moves us to honor what we call “round number” anniversaries? Why is a child’s eighth birthday seemingly a less significant event than their first? Why is a 15th wedding anniversary more cherished than a couple’s 12th?

Regardless of our inherent motivations, the 10th anniversary remembrances of the 9/11 attacks have already begun. Some see the installation within the 9/11 Memorial Museum of the FDNY truck crushed by debris from the Twin Towers as an unofficial beginning of the remembrance events.

One such event surrounds the ceremonial first pitch of the Little League World Series championship game Aug. 27 in Williamsport, Penn. New York City firefighter Michael Cammarata and 9-year-old Christina-Taylor Green were posthumously honored.

In 1991, Cammarata made it to the Little League World Series as a rightfielder for a Staten Island team. Ironically, he wore uniform number 11.

Green, a Little Leaguer and the granddaughter of former Philadelphia Phillies manager Dallas Green, was among those slain in Tucson, AZ, by the same gunman who wounded Rep. Gabrielle Giffords. Green would have turned 10 this Sept. 11.

For many Christians, there is added significance to this year’s remembrance: Sept. 11 falls on a Sunday. The General Assembly Mission Council has made worship materials available for congregations.

Here in New York, Moderator Cynthia Bolbach is set to preach at First Presbyterian Church of Brooklyn, a congregation directly under the smoke trail that blew to the east, away from the burning attack site.

At First-Brooklyn, as in other faith communities, there will no doubt be tears and prayers and questions ― tears for those who perished, prayers for their families and for peace, and questions about Islam, a religion too many Americans still do not understand.

It was this lack of understanding that helped fuel much of the vitriol surrounding last summer’s announcement of plans to build a mosque and cultural center in an old department store a few blocks from Ground Zero.

This same lack of understanding contributed to the creation of Prepare New York by a coalition of interfaith organizations.

Directed in part by Presbyterian Elder Annie Rawlings of the Interfaith Center, Prepare New York seeks to shift the discussion from one of fear and mistrust to one that celebrates New York’s extraordinary diversity of religious freedom and expression.

In an email, Rawlings outlined the coalition’s efforts: to address the compelling “something” about this particular anniversary felt by many, particularly New Yorkers.

The coalition aims to “serve the need to ‘discuss’ what happened while caring for those still wounded by the events.” There is also an awareness of those who might also stir up old hatreds.

Prepare New York’s tools include the promotion of civil dialogue, education about religious pluralism, support for the Muslim and Sikh communities and coordination of events on the day of the anniversary. Prepare New York is advised by September 11th Families for Peaceful Tomorrows and the 9/11 Community for Common Ground initiative.

The coalition’s outreach includes several components:

- Media outreach, including social media, media training for religious leaders and the film “We the People,” available on the group’s website

- “Ribbons of Hope,” a project inviting everyone from New York and around the world to bring ― or send ― a ribbon to Battery Park, at the foot of Manhattan, between Friday, Sept. 9 and Sunday, Sept. 11. Participants are asked to write on a ribbon a thought or prayer or hope for the healing of the city and for the whole world.

- On Monday morning, Sept. 12, religious leaders will dedicate the Prepare New York Tapestry of Ribbons. It will then hang in prominent public places around the city in an effort to continue the dialogue of inclusion, compassion and celebration of religious diversity.

- Study and discussion materials prepared by the Tanenbaum Center

- “Coffee Hour Conversations” designed as an all-encompassing umbrella for groups to bring in “a speaker such as an Imam talking with a church or synagogue during the coffee hour or lunch following worship.”

“I have met some amazing, inspiring people through this effort,” says Rawlings, “particularly the people who have turned their experience of bereavement, or trauma, into work for peace.”

Prepare New York’s mission is perhaps best exemplified by Megan Bartlett. An EMT from Brooklyn, she was among the first responders to spend extended time at the “pile.” Her experiences prompted her to establish Ground Zero for Peace — 9/11 First Responders Against War, an effort to build friendships between U.S. and Afghan first responders.

Prepare New York encourages Muslim leaders to meet with other faith groups before or after worship. —Photo courtesy: Prepare New York

A “Coffee Hour Conversation” may be on the menu of 9/11 remembrances still being planned by South Salem Presbyterian Church, located about an hour’s drive northeast of Ground Zero. The 9/11 tenth anniversary is dredging up many dormant memories and emotions.

One family’s story jumps out for South Salem member Billye Zoa Steinnagel. In an email, she recalls the family had a young son of 10 or 11 whose father worked for an accounting firm in the destroyed towers.

“The father got out alive,” writes Steinnagel, “but there was no longer a job for him. As a middle-aged man with a son almost ready for college, he had to start his professional life all over again, beginning his own small firm. The family lost no one but was greatly affected. In that case, the son felt tremendous pride in his father’s survival and resilience.”

9/11 memories come flooding back on two fronts for Carolyn and Bill Patterson. They live in Manhattan but also spend time in the South Salem area.

By email, Carolyn writes that her husband still shudders at the memory of his morning meeting that day: a meeting that was almost scheduled to happen in the collapsed Five World Trade Center.

With security concerns having shut down the city’s mass transit system in the wake of the attacks, Carolyn describes how her Manhattan congregation, Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church, set up a water table on the sidewalk, helping refresh the legions of people forced to walk the five miles uptown from Ground Zero and the surrounding financial district to their homes on the Upper East Side.

But Patterson most vividly remembers the story of her friend, Denise Rabinowitz, who worked at Depository Trust. During the attacks, Rabinowitz could not reach her husband by phone. Not getting her call through saved a few minutes and, as Patterson believes, her friend’s life.

“She proceeded to ignore the announcements to stay put and helped an elderly colleague down many flights of stairs to the ‘mezzanine’ level where people working on upper floors had to change elevators.” Rabinowitz described how her elderly colleague becoming exhausted, saying he could not go on any longer, imploring her go on ahead alone.

“At that moment, an elevator door opened,” relays Patterson. “Ignoring the usual wisdom, Denise led him into that elevator and it went straight to the ground floor without incident. They headed to the nearest exit in the midst of a terror-crazed crowd and, just as they were about to squeeze through the door, they were pushed aside. Seconds later a chunk of the building fell in front of that entrance. They would have died had they not been pushed out of the way. They found another exit and took refuge under a parked car. They eventually were found and led to safety, shaken but alive.”

‘Still a lot of healing’

“Ten years later,” writes the Rev. Chip Andrus, “there is still a lot of healing that needs to take place.”

He is South Salem’s new pastor, just a handful of weeks on the job he assumed June 27.

“The issues are so complex and the stories so numerous,” he writes, “it is almost overwhelming. Even if someone did not lose a family member they are only one degree away from the tragedy.”

Andrus was in Louisville on 9/11. For the past four and a half years he’s served in Harrison, Arkansas.

“Being here is much different. There is a strange disdain by many as to how the rest of the country looks at 9/11, especially in reference to the memorial and the wars (in Iraq and Afghanistan).”

Andrus hopes the South Salem experience can be a conduit for those people still needing to sort-out lingering issues. “There are mixed emotions about people from other parts of the U.S. doing memorial services but this has inspired us to do something more than just a service here.”

He remains optimistic. “I do think the response and creativity of the people here will help in the healing process.”

Ending needed

Logo of 9/11 Memorial and Museum —Photo courtesy: 9/11 Memorial and Museum

Ten years later, the 9/11 attacks still evoke very personal emotions for us New Yorkers.

Without question, we understand that 9/11 is even more personal for those who lost a loved one in the attacks that day ... or on the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan.

Ten years may be a long time to live in the shadow of a tragedy, but as long as the tragic results of extremism and terrorism persist, that shadow will persist.

Each pronouncement from the Department of Homeland Security ― created in the wake of the attacks ― keeps 9/11 in our consciousness.

Thus, in the interests of safety and peace of mind, we will continue removing our shoes, belts and metal objects at airports as we have our bodies scanned before boarding our flights.

Each chorus of emergency vehicle sirens is a potential cue for jogging memories of that tragic morning.

So, we will continue ― consciously or unconsciously ― to profile our fellow humans by Homeland Security’s campaign: “see something, say something.”

We will continue trying to heed some advice first offered by Britain at the onset of Hitler’s aggression in Europe: “Keep Calm and Carry On.”

When writing longer pieces, I like to use little phrases called sub-headlines to separate the sections, providing brief pauses in your reading experience and signaling what lies ahead. Should I draw a blank searching for the proper phrase to fit a particular sub-head, I’ll park a place-holder phrase in the space until a better phrase comes along.

In this instance, “something better” has yet to materialize. So, for now at least, it’s “Ending Needed.”

And it is forever personal.

Jim Nedelka is a radio news reporter in New York and an elder at West-Park Presbyterian Church in Manhattan.