“Give us Free! Give us Free! Give us Free!”

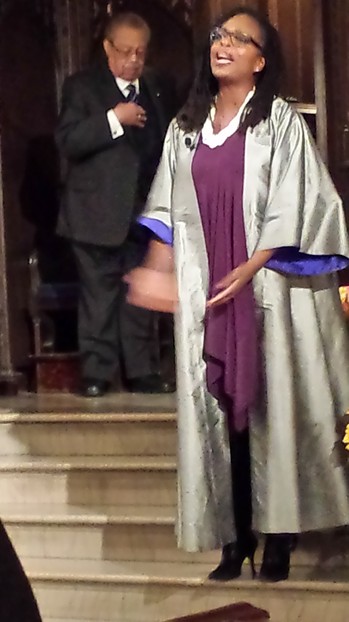

At this point in her sanctifying of 193 early-19th Century members and congregants of the Spring Street Presbyterian Church here, the Rev. Jacqueline J. Lewis, pastor at Middle Collegiate Church, paused in her invoking of the Amistad mutineer’s cry at his trial, looked up into the ceiling of New York’s First Presbyterian Church, then concluded: “Give us Free!”

She, along with those gathered on the blustery afternoon of Sunday, Oct.19, were memorializing the decedents ― including 75 children ― whose bones were discovered during a December 2006 construction accident on the church’s former site at the southeast corner of Spring and Varick Streets.

There, lying in the vast hole opened up by an errant backhoe ― the also-departed church’s long-forgotten burial vaults ― were the commingled remains, coffin plates and other funereal items of a congregation that, during the era when slavery was still legal in New York State, established a foothold for Civil Rights on the western edge of the city’s notorious Five Points neighborhood.

Befitting the progressive, abolitionist, integrated congregation which began admitting African-Americans to full membership in 1820, seven years before New York freed the slaves within its borders, not all the bones uncovered that day were those of European ancestry.

And, save for United States Senator Nicholas Ware, ironically from the then-slave state of Georgia who died in 1824 while visiting New York City, and the actor, Edwin Forrest, none of those comingled in death were once rich and/or famous.

From its founding in 1810, a half-century before the first shot of the Civil War was fired at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, Spring Street Church championed societal change. The persistent congregation:

- Opened their first sanctuary in 1811;

- Survived the yellow fever epidemic of 1822, which claimed the lives of four children of co-pastor Samuel Cox;

- Weathered co-pastor Cox’s 1825 secession, along with several members, to form a new Presbyterian church seven blocks away;

- Rejoiced when New York State freed the slaves in 1827;

- Recoiled in 1834 when anti-abolitionists, acting on a rumor that a mixed-race wedding had occurred in the church, ransacked the manse and burned the original sanctuary;

- Rebuilt on the same site, opening its second sanctuary in 1836;

- Became a depot on the Underground Railroad;

- Staved-off the impoverished conditions of its neighborhood which fueled rumors of the congregation’s death in the late 19th and again in the early 20th Century; and

- Beat-back the post-WWI flu epidemic.

While Spring Street ― never a wealthy congregation ― survived several economic booms and busts, including the Great Depression of the 1930s, it could not survive the enormous societal changes of the early 1960s occurring within its own neighborhood.

Thus, two weeks before Thanksgiving in 1963, with Spring Street’s octogenarian pastor having recently passed away, the session down to a lone active member and its heating plant operating on one lung, the Presbytery of New York City placed the church under care of First Presbyterian Church.

As the Rev. Jon Walton, current pastor of First Church, recalled for the crowd, the move brought Spring Street Church full circle, returning the church to the bosom of the congregation which had nurtured it during its inaugural year.

When First Church accepted the Spring Street Session’s final minutes on behalf of the presbytery, turned out the lights on its 153 year history and closed the church, the faint hope remained of reopening the sanctuary doors “should the neighborhood change.”

That hope lingered for three years but a 1966 fire prompted the building’s razing for a parking lot (which spawned its own colorful history: ties to the Genovese crime family uncovered during the 1980’s New York City Parking Violations Bureau scandal, escapades detailed in a May 1988 New York Magazine article by Nicholas Pileggi nymag.com/news/features/crime/46610/)

Flash forward 40 years and one month to the week before Christmas 2006: a contractor’s backhoe breaks through the parking lot’s tarmac and focuses the limelight away from the Donald’s pending 45-story Trump SOHO hotel.

With the long-forgotten Spring Street congregation once again raised on the minds of New Yorkers, and with memories still fresh from 1991’s rediscovery of the African Burial Ground within the same general neighborhood, what secrets would the bodies entombed below contain?

That contractor’s backhoe kicked-off a seven-and-half year sometimes-uphill odyssey of exploration, archeology, theology, red tape, forensics and genealogy into the lives of a congregation.

Finally last summer, their life’s work completed some 175 years into their after-life, the Rev. Agnes Blackmon of Westminster-Bethany Church stood graveside within the historic beauty of Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, blessed the bones of Spring Street Presbyterian Church ― men, women and children of all colors who lived their faith for benefit of people of all colors ― and committed them (hopefully) to their final resting place.

The Rev. Agnes Blackmon of Westminster-Bethany Church leads a graveside service in Brookyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, blessing the Spring Street remains. —Courtesy of Westminster-Bethany Church

Death have no mercy

Hark! A voice, the darkness choosing,

Calls my new born soul away.

Lately, launched, a trembling stranger,

On the world’s wild boisterous flood,

Pierc’d with sorrows, tossed with danger,

Gladly I return to God.

---from Lines on the Death of a Child, 1829

Death was no stranger in early 19th-Century New York, especially among children.

Death visited frequently, claiming its victims primarily through illness and diseases that, today, are often only known through their archaic descriptions.

Infant mortality was common, even reaching into the homes of Spring Street’s co-pastors: two children of the Rev. Samuel Cox died within a day of each other while the Rev. Henry Ludlow buried four children at an early age as well as among his extended family. The poem Lines on the Death of a Child (excerpted above) was composed to honor these young angels.

According to Reade Ryan, a ruling elder of First Church who is also an attorney, New York City is a stickler when it comes to bones or other indicators of a burial that are discovered during the city’s seemingly never-ending building efforts.

Thus, later in December 2006, when the Medical Examiner determined that no foul play had resulted in the Spring Street remains, the NYPD reached out to New York City Presbytery’s then-Executive Presbyter Arabella Meadows-Rogers, who turned to ruling elder David Pultz to represent First Church on a committee being set up to memorialize the Spring Street burial site. When Meadows-Rogers stepped away for medical reasons in 2009, Pultz was elected chair.

During the Oct.19 memorial service, Pultz quoted Rev. Cox from the 1820’s, “Slavery cannot exist much longer and well know that.”

It was Cox, stated Pultz, who championed full church membership for African-Americans in 1820, who integrated Spring Street’s Sunday School two years later and who laid to rest Georgia Senator Nicholas Ware in 1824.

“Initially,” said Pultz, “Ware was thought to have been interred in Queens (at Grace Episcopal Church) but was actually found in the Spring Street vaults with a name plate.” (This, along with other name plates and artifacts, were on display following the memorial service.)

Pultz, who is producing a documentary about the Spring Street saga, said his committee was fascinated that so many Spring Street families, “most of whom,” quoting pastor Henry Ludlow, “cannot afford or hire a pew in poor city churches” were able to purchase space in one of the four Spring Street vaults.

Pultz thanked the Rev. Blackmon for officiating the graveside reburial service this past summer at Green-Wood cemetery. Built in 1838 and located in Brooklyn ― a separate city during the years the Spring Street vaults were active between 1821 and 1846 ― Pultz noted that Green-Wood was the committee’s first choice for reburial.

Forensic researcher Meredith Ellis and David Pultz with some of the remains recovered from Spring Street. —Jim Nedelka

“Green-Wood provides some historical significance,” explained Pultz. “George Washington fought the Battle of Brooklyn (sic) on the site…an event some (Spring Street attendees) could possibly have remembered.”

Pultz closed his eulogy with a selection from Walt Whitman’s, Crossing Brooklyn Ferry:

“Flood-tide below me! I watch you face to face…

I see you also face to face.

…how curious you are to me!

I am with you, you men and women of a generation, or ever so many generations hence:

Just as I am refresh’d by the gladness of the river and the bright flow, I was refresh’d.”

Jim Nedelka, a frequent contributor to the Presbyterian News Service since 2007, is a ruling elder at New York’s Jan Hus Presbyterian Church & Neighborhood House. He most recently profiled Rev. Lala Haja Rasendrahasina, a 2014 Presbyterian International Peacemaker from Madagascar.