Songs and music are keys parts of typical Presbyterian worship services, but exploring why these elements are important can be an interesting lesson.

Singing together unites people across time and boundaries, said the Rev. Carla Pratt Keyes, worship leader at the Association of Presbyterian Church Educators annual event here.

Coming together to sing is an act of compromise: people agree to sing the same lyrics in the same tempo, Keyes said on Jan. 28.

“When we sing together, we join our voices as if joining hands,” forming the body of Christ, she said.

This oneness from singing has long been a part of spiritual life. Reading the account of the Last Supper in Matthew 26:26-30, Keyes noted that the supper ends with the disciples singing: “When they had sung the hymn, they went out to the Mount of Olives.”

Congregational song helps us respond to the events and people in our lives.

“Our songs remind us who we are and whose we are,” Keyes said.

Songs are a blessing, but the blessing doesn’t end with us, Keyes said. When we sing, we can bear a blessing to God, who gives us voices, grace and love. Singing together is a concert for God.

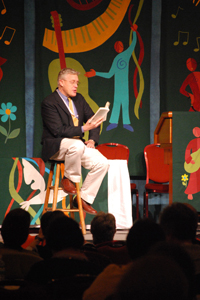

Following the worship service, the Rev. Michael Lindvall proceeded with the day’s plenary session. Lindvall is a pastor and an author known for his engaging stories.

Lindvall has lived in New York City for the past eight years, and in that time, he has had the chance to meet more Jews and learn more about Judaism. He said he appreciates Judaism’s tradition of storytelling and Jews’ dedication to what he called “doing Judaism.”

The routines and traditions of the faith — keeping kosher, celebrating bat and bar mitzvahs and observing Shabbat — are practices that express beliefs.

Many Christians, on the other hand, have tilted the belief/action scale more to the belief side, Lindvall said. He stated that he in no way was diminishing the importance of theology, but said, “in our zeal for ideas, we have perhaps neglected practice,” such as prayer, song and celebration.

Lindvall also spoke of Jonathan Sacks, chief rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth, and his description of faithful questioning.

Having faith does not mean having no questions.

“Answers only come when you actually entertain the possibility of learning something,” Lindvall said.

Faithful questioning also involves the realization that learning happens by living and doing. There is no theoretical way to learn how to ride a bike — you just have to throw one leg over the seat and pedal.

“The road itself is the teacher,” Lindvall said.