Sometimes necessity is the mother of reinvention.

First Presbyterian Church of Centralia, south of Olympia, Wash., was a typical old downtown church. As such, it faced the usual old downtown church problems of shrinking numbers, aging members and little idea of how to make the church appealing to younger generations. Then something happened that — literally and figuratively — shook everything up.

When an earthquake struck the area in 2001, the resulting damage to the church sanctuary left the building unsafe. Repairs were estimated at $500,000 to $1 million.

The church had to make a decision on how to move forward, and the 200 or so members ended up moving to a new building.

The congregation was nomadic for awhile. Members met for about a year and half in an empty outlet mall until that space was no longer available. They then met temporarily at the local high school. Around this time, the pastor was also planning to retire.

The current pastor, the Rev. Jim Dunson, arrived in 2006. Dunson was from the Olympia area and had heard about this church meeting in a mall. He was intrigued by the challenge of leading this congregation.

When Dunson arrived, the church was considering the purchase of an empty grocery store shell and had just started a capital campaign to raise funds.

The congregation raised $1.4 million in that campaign and bought and renovated the property, holding its first service in 2007. But the new building was just the start of the work, Dunson said.

“When I got here, my estimate is that 70 percent of the congregation was over 70 years of age and we had about 135 average Sunday attendance,” he said. “What was unique was, thanks to the situation with the building, it had encouraged the members to think in new ways. Change is not something people deal with well, but they were open to it. They knew they needed to change to survive.”

Still, while the members of First were more open to change than some congregations, not every idea was met with enthusiasm.

“The change in name from First Presbyterian Church to Harrison Square was met with mixed response,” Dunson said.

Harrison Square is the name of the shopping center anchored by the church. The belief behind the name change was that it would not only reference to the location but was also a sign of the fresh start approach the church was taking.

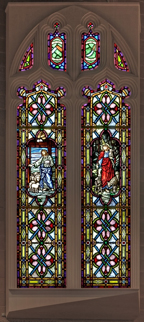

While they were open to change and accepted the new name, there was one thing the older church members were adamant on keeping — the stained glass windows from their old building, built in 1929.

At first, Dunson asked why.

The new building cost $6 million, and the church still owed $2.6 million.

“I asked them why they wanted to spend so much on those windows when we had all this other debt,” Dunson said. “They told me they were important. They raised $100,000 on their own to move them, install them in the new sanctuary, and have them backlit. It was worth it in the end. It links the past to the future and it hasn’t taken away from the focus of what we’re trying to do.”

But the real work involved taking a look at the church itself and its role in the community.

“We focused on the question of ‘What are we? What is our mission and vision?’” Dunson said. “We asked, ‘If this church didn’t exist, would it impact the community?’ and the sad thing is that a few years ago, the answer was no. So we wanted to think about what we needed to do to have an impact.”

The first step was re-evaluating how things were done. As with most Presbyterian churches, functions were designated to committees headed by session members. But session members rotate, disturbing the continuity of programs, so staff people were put in charge of the four areas of focus within the church — fellowship, discipleship, service and outreach. Session members oversee these staff members, who handle the day-to-day work.

Some of the programs started by Harrison Square: Simon’s Plot, a community garden on the church property; a basic needs ministry to provide food and diapers; and CAST, (Christian and Student Theater), a group of 30 grade school and high school students who put on Christian dramas three times a year. There are also plans to offer a community Bible study program to combat Bible illiteracy.

“We’re concentrating on fellowship now. Connectivity is one of the most important things to grow in the community,” Dunson said. “We’ll do dinners and such, but what we’re really working on is forming connection points. Our goal is to get people coming in connected to groups with common interests. Church transformation beings when people find authentic spiritual community.”

Because of Harrison Square’s commitment to thinking differently, the church is setting an example for other congregations, especially those facing similar “declining church” issues.

“This is a reinvention of an old downtown church in some new and exciting ways,” said Lynn Longfield, executive presbyter for Olympia Presbytery. “In addition to their creativity and courage, they’re focusing on education and deepening the spiritual life of the church.”

What’s perhaps more amazing according to Dunson is that there is little or no budget for any of these programs. Even the staff members who run them are mostly volunteers, and it’s only their creativity and ability to mobilize volunteers from the congregation that helps them succeed.

While the total membership has stayed about the same, Dunson tells church members not to get discouraged by those numbers. Losses to deaths and moving are being negated by gains, and Sunday attendance is up. In February 2009, the church averaged 164 people every Sunday, and in February 2010, it averaged 205 per Sunday.

Because it has seen so much success, Harrison Square has a new vision of being a place where other churches can come for training in outreach and community involvement. The church has secured several small grants and is putting together a program about sharing Christ in the 21st century. It will also host three all-day programs this year and hope to get about 50 attendees.

“They would like to share what they’ve learned and become a regional hub of evangelism education for other area churches,” Longfield said.

Toni Montgomery is a freelance writer in Statesville, N.C., where she is also secretary for First Presbyterian Church.