An interagency delegation from the Office of the General Assembly (OGA) and the Presbyterian Mission Agency (PMA) is returning to Juneau, Alaska, this weekend to attend a Formal Service of Acknowledgement, Apology and Commitment to Reparations. The apology is one of more than a dozen steps directed by the General Assembly last summer.

As reported in September, “The 225th General Assembly approved an overture to meaningfully address the wounds inflicted on Alaska Natives, who were directly impacted by the sin of the unwarranted 1963 closure of Memorial Presbyterian Church, a thriving, multiethnic, intercultural church.” The United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. was also responsible for dismissing Memorial’s pastor, the Rev. Dr. Walter Soboleff, which caused further harm to Native communities in Juneau.

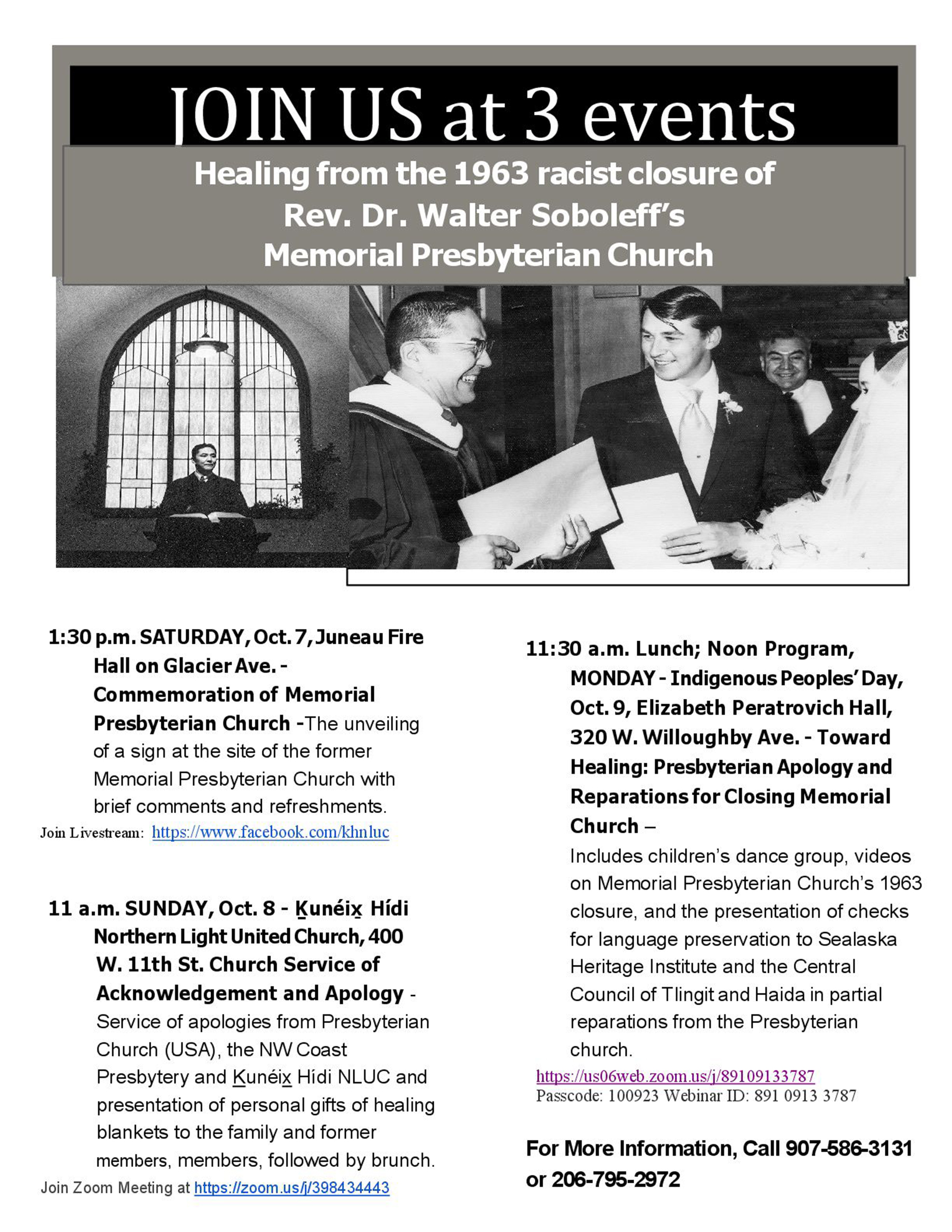

Events poster for Oct. 7-9, 2023, Juneau, Alaska. Courtesy of the Presbyterian Mission Agency.

The formal Service of Acknowledgement and Apology is scheduled for 11 a.m. Alaska Daylight Time on Sunday, October 8, at Ḵunéix̱ Hídi Northern Light United Church, with apologies by the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), Presbytery of the Northwest Coast and Ḵunéix̱ Hídi Northern Light United Church to be followed by “the presentation of personal gifts of healing blankets to the Soboleff family and former members of Memorial Presbyterian Church.”

Other events planned for the weekend include the Saturday unveiling of a sign at the site of the former Memorial Presbyterian Church and a Monday Indigenous Peoples’ Day program, “Toward Healing: Presbyterian Apology and Reparations for Closing Memorial Church,” that will include a children’s dance group, videos on Memorial’s closure and “the presentation of checks for language preservation to the Sealaska Heritage Institute and the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida in partial reparations from the Presbyterian Church.” Conversations are ongoing about PC(USA) support for the creation of a totem pole showing the story of Memorial Presbyterian Church and Rev. Soboleff.

In addition to the $100,000 in partial reparations being provided by PMA for language preservation and revitalization efforts, General Assembly overture RGJ-09 calls for PMA to provide $200,000 in the name of Memorial Presbyterian Church to the Presbyterian Foundation Native American Church Property Fund.

This weekend’s events come six weeks after an earlier listening and planning trip to Juneau by the interagency delegation.

Sasha Soboleff and Royal DeAsis participate in one of the first discussions between the interagency delegation and the Healing Task Force. Photo by Jermaine Ross-Allam.

“The primary function of the upcoming trip is to give an official apology from the local Presbyterian congregation, mid council and national church,” said the Rev. Jermaine Ross-Allam, delegation member and director of the Center for the Repair of Historical Harms in PMA. Ross-Allam is also lead writer for the national church apology.

In acknowledging the grievous harm the closing of Memorial caused Native communities in Juneau and the Soboleff family, the apology also addresses the denomination’s longstanding embrace of white supremacy culture in Alaska.

The Rev. Bronwen Boswell, Acting Stated Clerk of the General Assembly, will read the apology.

“As soon as I heard about all this work entails, I knew how important it is that the stated clerk be there,” she said. “We have to come to terms with, even in our trying to be faithful, we’ve done some incredibly hurtful things. This is a small step in trying to repair that damage.”

General Assembly overture RGJ-09 grew out of work by the native ministries team at Ḵunéix̱ Hídi Northern Lights United Church, a United Methodist and Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) congregation, with the overture being sent to the assembly by the Presbytery of the Northwest Coast.

Dr. Dianna Wright, director of Ecumenical Relations in OGA and a member of the interagency delegation, said the August visit “focused on listening to the witness of the Soboleff family, the church members and the community, to hear their stories and discover what it means to apologize and what an apology looks and feels like. We discovered that and more.”

Members of the Healing Task Force, members of the Soboleff family and experts in Tlingit and Haida culture talked with the delegation about Native history and contemporary life, imparting knowledge that helped shape the apology and reparations process.

“I walked away from the first trip with a sense of the strength and beauty of the indigenous cultures in that region,” Ross-Allam said. “The way they presented their cultures to us transformed my understanding of reparation and repair.”

He noted that members of the Healing Task Force, while recognizing the pain and trauma caused by the church, were intent on not being defined by the tragic period of protestant domination.

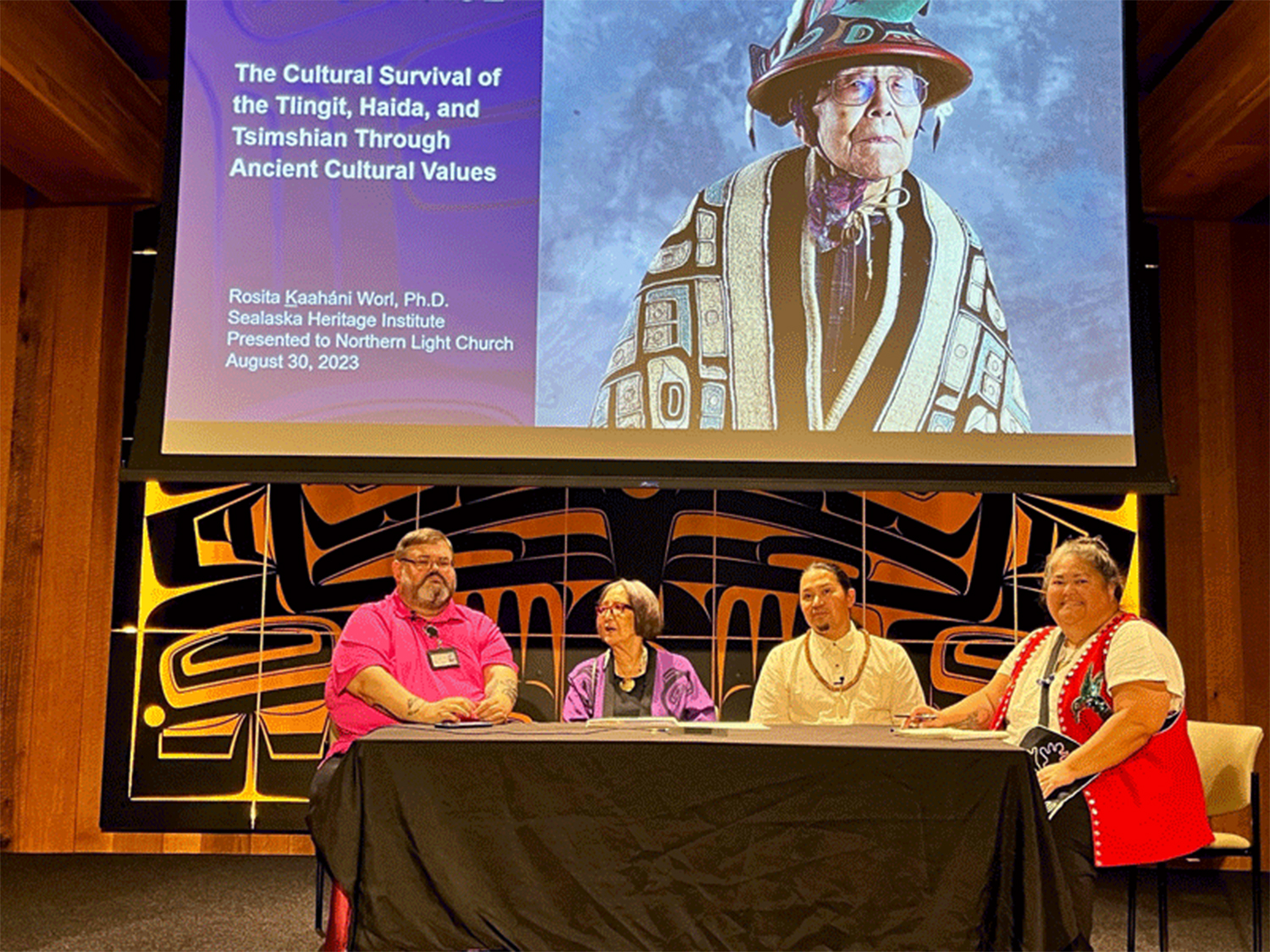

During a panel talk inside the Sealaska Institute’s Walter Soboleff Building, moderator Liz Medicine Crow, President & CEO of the First Alaskans Institute, said, “Knowing all these things that have happened before is incredibly important, but it is not the single identifier of who we are as Native people that these harms were done to us. Our identity existed before that, it exists now, and it will exist after. And it’s the now and the after of who we are as Tlinglit, Haida and Tsimshian peoples that is critically important.”

Ross-Alam, a scholar and social ethicist, said, “It’s very important for me to understand differences between who someone is to themselves and their own and what they are in the minds of people who thought they were going to dominate them into perpetuity.

“After [the church] apologizes, we’ll be in a position to partner with the broader community in Alaska about what [church-affiliated] boarding schools cost the communities and the culture, including the targeting of languages.”

Left to right: Richard J. Peterson, Rosita Worl, Lance X̱ʼunei Twitchell, Liz Medicine Crow, Sealaska Institute. Photo by Corey Schlosser-Hall.

Another speaker at the Sealaska Institute was Dr. X̱'unei Twitchell of the University of South Alaska, an Alaska Native Languages Professor. He said there are only eight Lingít master speakers alive today.

When Ross-Allam visited Juneau’s Saint Nicholas Orthodox Church, partly inspired by Wright’s ecumenical ministry, he talked with Father Maxim Gibson about the way Presbyterians went beyond other denominations in targeting indigenous languages for extinction.

Responding to this history, the Center for the Repair of Historic Harms is eager to help the Sealaska Institute’s initiative to increase the number of master language speakers. “We didn’t decide to give reparations to the Sealaska Institute for that,” Ross-Allam said. “The community did.”

He added that reparations need to be appropriate to the communities impacted by a specific injustice. “Reparations need to be related to what happened, who was affected and what needs to happen.” He favors a “call and response” model of reparations, where the church responds to an invitation from an affected community.

“In Alaska, I paid attention to the specific context of Memorial Presbyterian Church, but also to what happened throughout Alaska,” Ross-Allam said. “Richard J. Peterson, president of the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, told us that in Tlingit and Haida culture you make reparations and apologize at the same time. And you don’t apologize for something for which you aren’t ready to make reparation.

“[The church] needs to speak to the wider context of Presbyterian involvement in Alaska in this apology, but not apologize for those other things until it’s ready to make reparations for them.”

Wright said the apology needs to be accepted to be valid. Beyond it and the other planned events this weekend, “the church will need to continue its work of repairing the damage, so the community begins to heal. As [the interagency delegation] heard stories in Juneau, it became apparent that we have a lot to confess to and amend for.” Community-displacing urban renewal and the forcible removal of children from families are among the systemic injustices the church needs to study more.

Wright hopes that the listening, apology and reparations work in Juneau “puts the story in the larger context of the church’s historical role that caused this kind of harm there and in many other places around the world.

“I think this story has the power to help the church see, to name her history that contributed to this country’s racist behavior … so that we can begin to undo and tell the country and the world a new narrative. To say we were wrong, that the system that was created was and is an offense to God, is a beginning step to healing our land and God’s world.”

“This is not just the work of the Presbyterian Church,” Wright added. “Religious communities, government agencies, countries … all cooperated with each other to set in motion the ideas of white supremacy that created systems, laws, programs that marginalized groups of people because of their ethnic or racial identity. So, we must all work together to solve the problem.”

Boswell agreed there is a lot of work to do. On a recent trip to Salt Lake City, site of the next General Assembly, the acting stated clerk learned that the convention center is located in the historic Japan Town neighborhood, which was decimated by urban renewal. The Japanese Church of Christ, a PC(USA) affiliate since 2012, is located there.

“This sort of thing happened in a variety of ways in different cities,” she said. “We’re wondering what our faith can do to help with our civic duty.

“I hope this apology is a step,” Boswell added about the events in Juneau this weekend and Monday. “It’s not the end, it’s recognition of [past injustice] and the beginning of a better opportunity to work together.”